Philosopher Paul Virilio wrote of the integral accident — with technological advancement there comes a corresponding new accident. Planes beget plane crashes, electricity begets electrocution. Artificial intelligence has, in turn, delivered the AI hallucination. Lawyers do it, judges do it, our clients do it. When Mata v. Avianca came down — the ur text of lawyer AI hallucination screw ups — we defended the technology against critics, stressing that the problem in this case remained fundamentally human. It shouldn’t matter where the fake cite comes from… lawyers have an obligation to check their filings for accuracy.

Don’t hate the (video) game, hate the player.

Now, after a couple years of sustained hallucination embarrassments across the industry, we have to wonder if it’s time to start hating the game. It seems like they’re just not stopping and it doesn’t seem to matter if the sanctions are understanding or draconian. There’s another story coming out of last week:

Christine Lemmer-Webber described generative AI as Mansplaining As A Service, and I don’t know if an AI tool suggested telling the judge that there were attached cases that weren’t attached, but it raises the mansplaining bar.

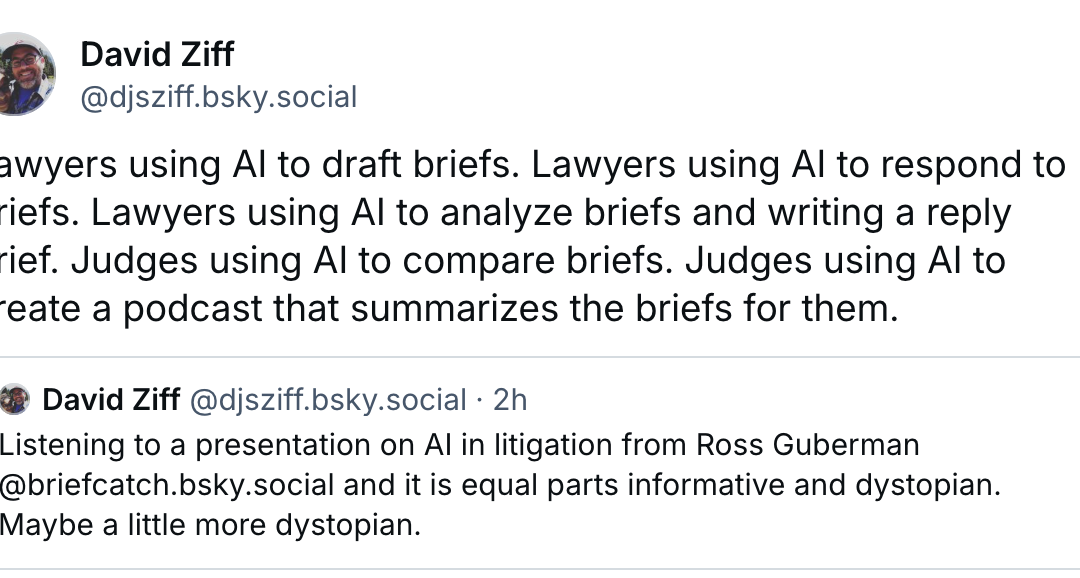

How is this still happening? There’s an interesting back-and-forth among law professors today:

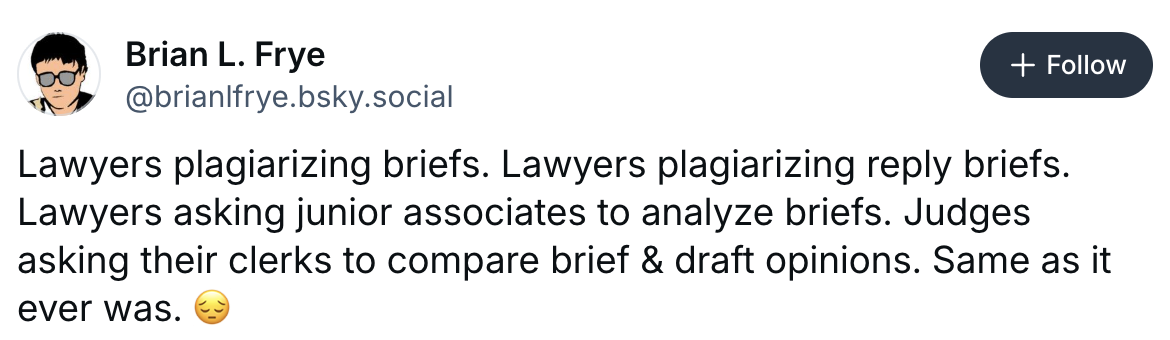

In response, Professor Frye states:

Which is fair. Plagiarism should be your friend in a common law legal system. Whenever an enterprising lawyer tries to assert copyright over their public filings, a puppy dies. But there’s an art to knowing what to properly copy to advance the client’s argument. Though even with a “human in the loop” — the industry polite phrasing for “you’re still responsible, dumbass” — does the human process of finding good material and copying it lose something when automated?

On a surface level, it shouldn’t. However the material gets there, the human checking it should make sure it’s right before it goes out the door.

But returning to Virilio, another of his core arguments was that speed changes the nature of an event. Applying this sort of dromological displacement to the process of writing, Virilio might say that these tools aren’t just typing faster, but changing what a “brief” (or “opinion”) even is. Is the brief merely the manifestation of the argument to the tribunal, or is it also the site of the lawyer’s thinking through of the argument. To the extent it’s the latter, automation collapses that temporal space. The lawyer doesn’t write with time anymore, as much as they write against it. When we talk about how AI accelerates the process, a lawyer’s conception of the workflow itself can change and the human act of tediously checking cites becomes so jarring when juxtaposed to the writing process that we look down upon it as an obstacle to be half-assed… or, probably inevitably, turned over to yet another bot.

The hype surrounding “Agentic” AI tends to suggest the industry has a hankering for this “GPT-sus Take The Wheel” approach. Truly Agentic AI is miserably inaccurate. Thankfully, most agentic applications in legal are can only very tenuously be called “agentic,” which may irritate marketing teams, but should make lawyers more comfortable. Regardless, the fact that we’re talking about Agentic AI as a goal is indicative of a desire to erode the human from the loop. There’s a fundamental difference between (1) the iterative process of querying the bot, checking the output, refining the query, checking the output, rethinking strategy, running the query again, checking that, and then moving to step 2 in a five-step workflow; and, (2) showing up after an AI churned through the five-step workflow uninterrupted and trying to reverse engineer the delivered work product to make sure it makes sense. Because the first option is where AI more or less exists as a legal tool now and the second is the “promise” of agentic.

And anyone who doesn’t believe there’s a difference between the two, consider how you would normally work on a brief with junior associates every day and assigning the brief, taking a three-week vacation, and then editing a draft for the first time six hours before it’s due. Those are two very different processes.

Which brings us back to the question: has AI made lawyers dumber? Is it just shining a light on lawyers who were already too careless, or has it changed the whole process in a way that creates more carelessness?

And if it is the latter, the answer isn’t to reject the technology. There may well be a catastrophic bubble bursting sometime soon, but the underlying technology will find a way to go on. How do lawyers adapt to this psychological reordering of the process? Like most continental philosophy, Virilio isn’t saying speed is necessarily bad, it just… is.

And understanding what it’s doing to you is half the battle.

Joe Patrice is a senior editor at Above the Law and co-host of Thinking Like A Lawyer. Feel free to email any tips, questions, or comments. Follow him on Twitter or Bluesky if you’re interested in law, politics, and a healthy dose of college sports news. Joe also serves as a Managing Director at RPN Executive Search.

The post Has AI Managed To Make Lawyers Even Dumber? appeared first on Above the Law.